As I, like so many other naturalists, have long kept a dated record of the natural events I witness occurring around me throughout the year, I was recently delighted to discover when and how the practice is able to be documented as beginning.

As I, like so many other naturalists, have long kept a dated record of the natural events I witness occurring around me throughout the year, I was recently delighted to discover when and how the practice is able to be documented as beginning.

One of the many joys of field guides, aside, of course, from their utility of identifying species, is perusing them out of pure curiosity to discover what manner of animals, plants, or whatever their respective subject may be are to be found in a given area (or even in existence, for that matter).

As mammals, we’re something of an anomaly. Most of our mammalian kindred species are well suited to, and indeed orient their lives around, the night. We humans, on the other opposable thumb equipped hand, have evolved – particularly in regard to our visual acuity – to fare much better in daylight. Therefore we have done all we can to make sure that those things that go bump in the night, as well as the more stealthy ones that don’t, aren’t concealed from us.

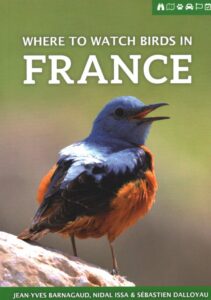

Chatting about birdwatching with my friend Miriam who lives in the Vichy area of France, I was reminded that not so long ago a new guidebook arrived from Pelagic Publishing that promises to direct its readers to the best spots in that nation for pursuing this favored ornithological past-time.