In 2018, when the Southern Resident Orca given the human name of Tahlequah by observers gave birth to a calf that soon died and that she subsequently carried on her head for seventeen days, endangering her own life in the process due to the difficulties the act caused in her eating enough to recover from the birth, journalists from around the world flooded the airwaves and Internet with stories of her mourning, her sorrow, her grief, how much she was like a human mother whose own child had died.

In 2018, when the Southern Resident Orca given the human name of Tahlequah by observers gave birth to a calf that soon died and that she subsequently carried on her head for seventeen days, endangering her own life in the process due to the difficulties the act caused in her eating enough to recover from the birth, journalists from around the world flooded the airwaves and Internet with stories of her mourning, her sorrow, her grief, how much she was like a human mother whose own child had died.

But how does anyone know that any of this is correct? The closest relationship between orcas and humans is at the taxonomic class level of Mammalia. We live in completely different environments, have significantly different respective biologies, and have no common language through which we can communicate even the most rudimentary information about one another’s inner lives – assuming of course that orcas have anything recognizable to humans as an inner life, or even perhaps vice versa. And in the particular question of why Tahlequah was carrying her dead calf, do, and if so how do, orcas understand death itself?

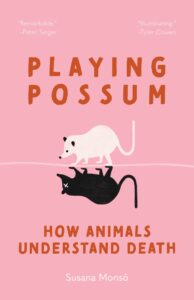

In her new book Playing Possum; How Animals Understand Death, Prof. Susana Monsó introduces her readers into the field of study named comparative thanatology. A very new field of study drawing into itself elements of ethology, comparative psychology, and the philosophy of science, comparative thanatology explores different understandings of the death in other species of conspecifics (members of their own species).

Proceeding slowly, in a remarkably intelligible, even personable, manner given the subject’s obscurity and complexity, Prof. Monsó guides her readers though the concepts – particularly those from the philosophy of science – necessary for a useful understanding and exploration of the subject. Combining presentations of concepts and ideas through examples centering on different species, with an unexpectedly down-to-earth writing style that even includes a surprising (and welcome) amount of gentle jesting), the reader’s understanding, and confidence, is steadily increased.

I’ve read more than a few books on the philosophy of science in my time, and most of them are, due to a whirlwind of jargon and mind-twisting concepts, as dense as a diamond. This one is different. It’s welcoming. It breaks challenging-to-understand concepts into understandable pieces. And – quite surprisingly given that the main subject if death – it’s entertaining, in the sense that upon concluding a chapter the reader is quite likely to find her or himself saying “Wow! That was fascinating!”

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.