When I think about all the people I know presently involved in science – either actively working in one of the many disciplines from biology to astronomy, studying to one day do so, or working in an occupation supporting the dissemination of discoveries therein or for the greater widespread understanding thereof – the majority who most readily come to mind (including our own daughter, presently studying biochemistry and biophysics) are women. However, aspiring to be well-read in the history of science as I am, I know all too well that up until relatively recently, this was not always so. And while, in the United States, for example, the overall number of women receiving STEM degrees is now higher than that of men, in some of the fields, particularly the computer sciences, engineering, and mathematics, women continue to be in a significant minority.

Indeed, looking back only a century, when women were just beginning to enter the sciences at the university level – but for all their efforts were often not granted the degrees testifying to the completion of their studies – there were still even a number of fields from which women were all-but-outrightly barred, or in which they faced such blatant dissuasion that pursuing meaningful studies was both impractical and unprofitable. Such was the world into which Dr. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin entered when arriving at Newnham College, Cambridge in 1919. It was a world, as Donovan Moore recounts in his What Stars Are Made Of; The Life of Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, in which – as well later as at Harvard University – she would repeatedly not only break through the institutional and social limitations placed upon her, she would, as the result of her inexhaustible determination and insatiable curiosity, leave barrier after barrier lying in heaps of rubble on the ground in her wake.

The eldest of three children born to an educated, upper-middle class family in Wendover, Buckinghamshire, England, Cecilia (out of respect, I will only refer to her simply by her given name in reference to her younger years) – as Mr. Moore explains – had the benefit of parents who did not believe in holding their daughters back from the acquisition of a full education. And while tragically deprived of her father at an early age due to Edward Payne’s untimely death, her mother Emma saw to it that Cecilia and her siblings were raised in an environment where education was given a very high priority.

Emma Payne having moved the family from Wendover to London when the children were still young, Cecilia attended St. Mary’s – a school for girls (at which Gustav Mahler was the teacher of music during her time there). She excelled in both the sciences as well as the humanities (indeed, her proficiency in classical Greek would one day come to be the source of much needed funding to allow her to continue her studies). But it was at Newnham where she truly began to shine.

It was from her room at Newnham one December night in 1919 that Cecilia ventured – with the officially granted permission required for a female student such as she was having been obtained to do so, it should be noted – to attend a lecture at Trinity College’s dining hall by Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington on the subject of his recently concluded observations of the solar eclipse that year that lead to the confirmation of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. As Mr. Moore describes it, it was a night of revelation, a night during which she “had an instant recognition of a life’s calling that years later would lead to unlocking one of the great mysteries of the universe.”

To disclose that Dr. Payne-Gaposchkin is responsible for the discover of the prevalence of hydrogen in the universe is not, by any means, to spoil the story of her life; most familiar with the history of astronomy should today be aware of this fact. That she was the first woman to receive a doctorate in astronomy from Radcliffe College, the first woman promoted to a full professorship at Harvard, the first to head a department there, and among the first – female or male – to undertake the studies in the then newly emerging field of astrophysics itself, might not be so well known. And they are the milestones, along with more intimate insights into her personal life – including her marriage to Sergei Gaposchkin, her life as a working mother, and the challenges both of these posed to her scientific work – by which Mr. Moore has structured this highly readable and surprisingly lively biography (truly, one might be forgiven for not anticipating that the life story of an astrophysicist – even a particularly accomplished one – to be the subject of a work that reads as excitingly and compellingly as the biography of a much more popularly known figure).

That the name of Payne-Gaposchkin is not the natural next one mentioned following the series “Copernicus, Newton, Einstein…” when those whose works have enabled us better to understand how this universe in which we all live physically functions is indeed a unfortunate state affairs. Fortunately, it is an (to put it graciously) oversight that Donovan Moore has done much to set right in his What Stars Are Made Of. It is indeed hoped that it is a book that will find a wide readership among both the scientific as well as the popular reading communities. Indeed, it is particularly hoped that it is a book that will find its way into the hands of younger readers, to inspire them never to allow themselves to be held back – by either institutional or societal limitations – from their inspired pursuit of knowledge, for in the life story of Dr. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin it is shown that when one reaches for the stars, they can – through exceptional study and effort – actually be obtained.

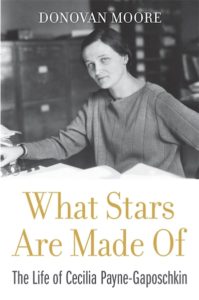

Title: What Stars Are Made Of; The Life of Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

Title: What Stars Are Made Of; The Life of Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

Author: Donovan Moore, with a foreword by Jocelyn Bell Burnell

Publisher: Harvard University Press

Format: Hardcover

Pages: 320 pp., w/ 58 photos

ISBN 9780674237377

Published: March 2020

Degrees of Arthur Stanley Eddington: 1

In accordance with Federal Trade Commission 16 CFR Part 255, it is disclosed that the copy of the book read in order to produce this review was provided gratis to the reviewer by the publisher.