According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “imperial” is defined as:

imperial (adj.) late 14c., “having a commanding quality,” from Old French imperial, emperial “imperial; princely, splendid; strong, powerful” (12c.), from Latin imperialis “of the empire or emperor,” from imperium “empire”

Looking a bit further into “imperium,” we find:

imperium (n.) “authority to command the national military forces,” in extended use “an empire,” 1650s, from Latin imperium “command, supreme authority, power”

Empire. Command. Supreme authority. Power.

In the early 19th century, these were the operational by-words of those who sought to control all possible parts of the known world in order to extract from them anything of economic value. And few could have been said to do this with greater efficiency and effectiveness than the East India Company (EIC). From their incorporation by royal charter on 31 December 1600, they expanded their reach across southeast Asia and eventually even into mainland China through the assiduous application of most every word that could be used to define imperium.

By the time that Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles, FRS, negotiated the transfer of Singapore to the EIC in 1819, the administrative effectiveness of the British imperial system had placed it in control of a sizable portion of the world. They were extraordinarily good at deriving profit – either monetarily or strategically – from every land they controlled.However make no mistake – their effectiveness was not the result of (as is sometimes simplistically portrayed) intentional arbitrary ruthlessness or cruelty, although both were often by-products; rather it was about organization and control – the more smoothly something could be managed, the more profitable it was likely to be. But while an emphasis on ultimate efficiency for the maximization of profit may be beneficial to a business enterprise, a government, or the former acting as the latter, its effects upon those who live under such rule are not always positive; even more so when those in question are unable to speak on their own behalf.

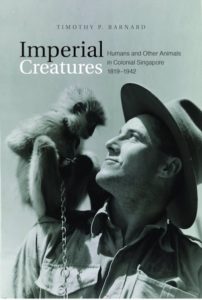

In his Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819–1942, Timothy P. Barnard approaches the study of his chosen time and place through the the lives of the animals – both wild and domestic – to be found there. Employing the multi-disciplinary approach from the relatively new academic field of human-animal studies, Prof. Barnard sets out “to explore the history of animals in Singapore to better understand how the imposition of colonial rule transformed an island.”

And transform an island the colonial government of Singapore did. Within less than a century of Raffles negotiating the transfer of control from the local chiefs to the EIC, an estimated “92% of the original forest cover had already been lost” to the creation of plantations producing cash-generating crops. Not surprisingly, vast numbers of species that were found on the island at the turn of the 19th century were locally extinct by the turn of the 20th. However, as so many of these species were scarcely recognized, or discovered only at the time of the their elimination, a focus upon them is of limited use in understanding Prof. Barnard’s larger purpose with this book. Histories of creatures for which substantial documentation is available are much more enlightening in such an enquiry. Thus, as he explains, while “much of the work at the intersection of human-animal studies in Southeast Asia has focused on charismatic megafauna […] In contrast, this work focuses on a wide variety of relatively uncharismatic and common animals, with considerable attention given to dogs, cattle, and horses.”

This is not to assume that the more “charismatic” species are ignored. Tigers, not native to the island but having found there way there, were quickly proclaimed the bête noire (well, bête noire et orange…) of the newly constituted Singapore. Hunted, tormented and tortured by members of the “Tiger Club,”, pitted against bulls for the “entertainment” of visiting dignitaries, and finally encaged in the zoo, where they were – for a time – fed live puppies for the amusement of zoo visitors, any tiger unlucky enough to live its life in colonial Singapore was doomed to an existence that was indeed nasty, brutish, and short. However as brutal as this all was, it is important to note that hat public opposition there was to some of these activities – particularly this last mentioned one – centered around the idea that such brutality was in fact brutalizing to those who witnessed it. The argument is indeed one with merit, and one that was played out in a much larger scope with the treatment of the island’s dogs.

Singapore’s rapidly expanded population of feral dogs, C. lupus domesticus, is given a particularly large portion of Prof. Barnard’s attention. Present long prior to the colonization, feral dogs quickly expanded in numbers along with the human population, becoming at first a nuisance and then a physical as well as psychological threat to the human inhabitants of the increasingly urbanized environment being established around them. How to manage this canine population became, and long remained, a topic of significant public debate. Adding to the complexity of this was the cosmopolitain population of the island – the British colonials viewed the dogs differently than the Chinese, and these differently than the Malays, Tamils, and Klings. However if order was to be established and maintained – and under the EIC and subsequently the British Foreign Office, it absolutely was – very clear-cut regulations needed to be established that would be able to be understood and followed by all. As a result, these regulations tended toward absolutism rather than nuance (this becomes a pervasive theme throughout the colonial period – and some might even say one that continues to this very day).

Designated periods of summary dog killing by publicly “employed” (if what were effectively bounty hunters could be so called) groups of club-wielding men, waxing and waning in scope and duration, were the predominant early technique, to be later modified to rounding up feral dogs for execution elsewhere. Of course, as the keeping of pet dogs became more popular in Britain and then spread to colonies, a shift in the attitudes of the colonials toward such bloody public activities lost favor – particularly when the dog killing squads would occasionally set upon a beloved pet in a front garden in order to claim an additional bounty. Then there was the rabies outbreak…

Also receiving particular attention by Prof. Barnard are the ponies and bullocks that pulled the small carts that were the backbone of public and commercial transportation in early colonial Singapore. What was proper and acceptable for their treatment had to be regulated lest the public would be witness to half-dead or untrained draft animals being beaten bloody by their drivers in the streets. This subject, while not commanding the public attention and debate quite to the level seen with the dogs, the interweaving of economic and social status, not to mention ethnicity, played a much greater early role here, particularly when juxtaposed with the regulations pertaining to the treatment of horses in the introduced activity of horse racing. Such a complexity of status divisions as quickly emerged regarding the ponies and bullocks was not equalled in relationship to the multi-faceted dog situation until much later in the period.

As might be expected, these above-mentioned examples are only a small part of the information and commentary presented by Prof. Barnard in this deeply researched, well annotated, and surprisingly (given the previous two qualities) readable book. While perhaps a bit academic for some tastes, Imperial Creatures should by no means be thought only to be of potential interest to those studying the colonial period in Singapore’s history and the human-animal interactions occurring there at that time. Indeed, the information Prof. Barnard presents in this book is widely applicable to subjects as varied as the history of natural history, psychology, sociology, political science, cross-cultural communications, and urban planning. It is therefore strongly recommended to all those with an interest in any of these subjects, as well as to those who are merely curious to discover a slice of the history of a time and place with which few today can be said to familiar, but from whence so significant a modern global city-state has emerged.

Title: Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819–1942

Title: Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819–1942

Author: Timothy P. Barnard

Publisher: National University of Singapore Press

Format: Paperback

Pages: 336 pp., w/ 23 b&w images, 2 tables

ISBN: 978-981-3250-87-1

Published: 2019

In accordance with Federal Trade Commission 16 CFR Part 255, it is disclosed that the copy of the book read in order to produce this review was provided gratis to the reviewer by the publisher.