When it comes to spectator sports, birding ranks somewhere in between bass fishing and reading. For while the watching and tallying of birds can be enjoyable, relaxing, invigorating, and even emotionally and spiritually restorative, the watching of others watching birds is anything but. Which is quite likely why, despite birding being the preferred hobby of quite literally millions, perhaps even tens of millions, of people all around the world; other than in England – where natural history is a part of the national culture in a way that it is no where else – you will not see birding represented in any significant way in the popular media.

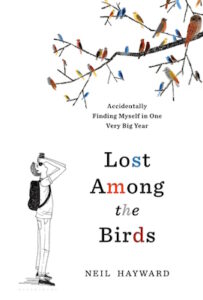

And if watching people watch birds is tedious, reading about people watching birds all too often proves itself even more so. While there have been some genuinely noteworthy books about birding (Peterson’s and Fisher’s comes quickly to mind), most of these tend to wrap the activity up with another topic – bird conservation, for example, or as part of a larger autobiography (a la Phoebe Snetsinger). Thus when the advance reading copy of Neil Hayward’s then forthcoming Lost Among the Birds; Accidentally Finding Myself in One Very Big Year, I was admittedly less than enthusiastic to begin reading it.

I’ll be perfectly honest; in the twenty odd years that I have spent among the birding community, I have met an untold number of genuinely delightful, warm, charming, quirky, intelligent, and eminently likable people. And while I consider myself more of a general naturalist than a proper birder, I do readily admit to keeping some semblance of a life list and – for the past year at least – submitting my bird sightings to Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird program. However there is one element of the birding community about which I have very mixed feelings: the big year.

For those who might not yet be familiar with this practice, at the most casual end of the spectrum it involves simply tallying all the bird species one sees and identifies over the course of a year in any given geographic area, be that area as small as one’s own back garden or as large as the entire world; however at the spectrum’s opposite end, it becomes an all-encompassing year-long quest, sparing no expense – economic, physical, familial, social, or emotional – in pursuit of the highest number of birds seen in a designated region.

And indeed, it is this latter form in which Mr. Hayward was engaged and about which the book revolves. All my past experience told me that less than half way through I should have found it tedious, closed the cover, and (due to my practice of not reviewing books I didn’t find interesting, useful, or enjoy) said no more about it. However much to my surprise, none of this proved to be the case. In fact, I thoroughly enjoyed it from the first page to the last.

Very much unlike too many others of the genre, Hayward’s Lost Among the Birds includes the crucial element of self-aware absurdity. He didn’t set out to engage in such an outlandish quest; he even repeatedly rejected it when proposed. In truth, it just, as they say, “sort of happened.” And that’s where it is at its most charming.

Vaguely Dantesque in its beginnings, Hayward’s own life had stalled; he was lacking both purpose and direction. To quote Longfellow’s translation of the words of the poet himself,

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.Ah me! how hard a thing it is to say

What was this forest savage, rough, and stern,

Which in the very thought renews the fear.So bitter is it, death is little more;

But of the good to treat, which there I found,

Speak will I of the other things I saw there.I cannot well repeat how there I entered,

So full was I of slumber at the moment

In which I had abandoned the true way.

A highly educated and professionally successful man, Hayward had reached his late thirties and found himself beset by not only uncertainty as to where his life’s path should next lead him, but also by untreated depression. Everything he had set out to do in life he had seemingly accomplished, but as with Dante, he had sleep-walked into his present state and found himself thoroughly lost.

Turning to birding – as so many, myself included – do in such times, Hayward soon found that he was not merely setting out to see a few birds, he was drawing upon his not inconsiderable resources to go find them in locations farther and farther from home. With a number of different elite level birders – particularly the then yet unmet Jay Vanderpoel – serving as Virgil, Hayward embarked on the path that would take him through all the American Birding Association’s circles of birding and eventually to the very farthest – and like Dante’s Caïna, coldest – birding destination in pursuit of birds for his list.

As for the “sinners” our pilgrim meets along the path, well, the English word “sin” is a common translation of the Greek word ἁμαρτία (hamartia) meaning “to miss the mark” to “to go outside the boundaries.” The birds Hayward most ardently pursues are sinners in that they have flown far off-course and ended up in areas, and even on continents, where they are beyond all hope of being able to breed or ever return. And as for the birders, they too are many times “outside the boundaries” of what would constitute a so-called normal life. (Ironically, Hayward repeatedly uses the word “normals” to refer to non-birders, a further reminder of his all-too-strong awareness that what he is doing is anything but).

And just as Dante had his Beatrice, Hayward too has an object for his affections – Gerri. Without Gerri, and Hayward’s repeated returning to his analysis of his feelings for her, Lost Among the Birds could have easily become just another self-recounted tale (albeit an unusually witty and well-written one) of an upper-middle class, well-heeled, middle-aged birder indulging himself in a monomaniacal hobby. Hayward’s feelings about Gerri, the conflict between his increasing desire to fulfill his birding quest and his understanding that in doing so he is putting his – and her – future happiness in jeopardy, is what gives the book the humanity through which it is able to so genuinely connect with its readers.

Through his intelligence and wit, his willingness to explain the hows and whys of birding for the benefit of those unfamiliar with them, his awareness of the absurdity of his own activities, and certainly not least his rediscovery of his own humanity, Hayward is able to to achieve in his Lost Among the Birds what few other books of its genre have been able to do: bring an enjoyable, intelligible explanation of elite birding’s most arcane activity – the big year – to an audience of both general readers as well as the “initiated” in a way that will directly appeal to them all.

Title: Lost Among the Birds; Accidentally Finding Myself in One Very Big Year

Title: Lost Among the Birds; Accidentally Finding Myself in One Very Big Year

Author: Neil Hayward

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Imprint: Bloomsbury USA

Format: Hardback

Pages: 416 pp.

ISBN: 9781632865793

Published: June 2016

In accordance with Federal Trade Commission 16 CFR Part 255, it is disclosed that the copy of the book read in order to produce this review was provided gratis to the reviewer by the publisher.