Let’s be honest – even the most social media skeptical amongst us is vulnerable, should we find ourselves waiting in a particularly long queue, stuck in non-moving traffic, waiting for a coffee or a meal, etc. – to pulling out one of the ubiquitous little electronic time thieves that we carry about on our person each day, tapping open Insta-Book-Red-Tok, and allowing our attention to be diverted while our cognitive abilities and mental health are slowly degraded. It’s difficult not to fall into this trap. Indeed, it’s designed to be that way as there are billions of dollars to be made by causing every man, woman, and child on the planet capable of seeing a screen to develop an addiction to the use of social media through the Pavlovian conditioning of those using it by leveraging with each scroll the user’s own hypothalamus to release dopamine, explained by this article from Mass General Brigham McLean Hospital as “a ‘feel-good chemical’ linked to pleasurable activities such as sex, food, and social interaction.” As the article continues “the platforms are designed to be addictive and are associated with anxiety, depression, and even physical ailments.” More than perhaps any other modern business, social media companies have proven very well that if you aren’t paying a company for a service you think you are receiving, you’re not the customer; you’re the product

Fortunately, we haven’t – yet – quite reached the Orwellian stage where the use of social media is both mandatory and enforced, although given the rapid demise of traditional forms of mass communication such as newspapers, magazines, broadcast television, and radio this may not be necessary as most of use may very well be “willing” (scare quotes added to emphasize the difficulty in ascribing free will to anyone acting under the effects of a chemical addiction) to do so rather than need to be made to comply. Myself, to borrow from Mr. Thomas, I’m not quite ready to go gently into that good mental night. In fact, I make it a practice of raging – quietly, admittedly – against the dying of the intellectual light by ensuring that I have a small book with me at all times when I’m away from home. Preferably pocket sized, these books have, over the course of this my journey, most commonly been from the Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford Very Short Introductions, and – when I can find well-preserved copies of them here in the former colonies far from their original country of publication – the Observer’s’ Book series. However, recently to these stalwart tools of intellectual and mental health defense, I have added the volumes of the Princeton Little Books of Nature series.

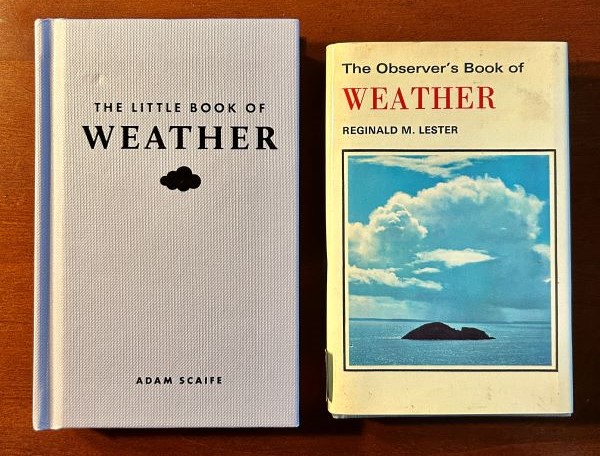

Modeled on the aforementioned classic British – and now unfortunately discontinued – Observer’s Book series, the Little Books of Nature at the time of this writing number eight volumes in total. Each volume is bound in a durable unjacketed hardcover format that, while being a just a bit larger than the Observer’s Book volumes, is still of a size that allows them to fit easily into a jacket pocket. Rather than being organized using long chapters, the Little Books‘ content is arranged into relatively short ones, and each chapter in itself is divided into very short, tightly-focused sections that most commonly are no longer than two pages in length. Such short sections enable the reader to read the entire section and give consideration to the full-color illustrations, maps, graphs, or charts supporting it within a few minutes.

Modeled on the aforementioned classic British – and now unfortunately discontinued – Observer’s Book series, the Little Books of Nature at the time of this writing number eight volumes in total. Each volume is bound in a durable unjacketed hardcover format that, while being a just a bit larger than the Observer’s Book volumes, is still of a size that allows them to fit easily into a jacket pocket. Rather than being organized using long chapters, the Little Books‘ content is arranged into relatively short ones, and each chapter in itself is divided into very short, tightly-focused sections that most commonly are no longer than two pages in length. Such short sections enable the reader to read the entire section and give consideration to the full-color illustrations, maps, graphs, or charts supporting it within a few minutes.

And therein lies their particular value as an antidote to one of the great plagues of our modern age. In the same time that it takes to draw out a mobile phone, open a social media app, scroll for a few minutes, and perhaps leave a short comment or a couple of “likes,” someone carrying one of the Little Books of Nature can flip to where they left off and learn something important, interesting, and far more enduring than the latest meme or pseudo-scandal. Take for example the first chapter, “What is a fungus?” from the recently published The Little Book of Fungi by Britt. A. Bunyard. It is divided into six short sections, each two pages in length, each with lively, interesting, and helpful accompanying illustrations. Section titles include “How many fungi are there?,” “Primitive, but highly specialized,” and “Morphological classification.” At two pages in length, such topics are easy to read and begin to contemplate during the span of time it may take to await the making and delivery of your morning cappuccino or for the two people in front of you at the market to have their grocery items tallied, bagged, and purchased. And as the organization of the chapters and sections in each volume is carefully edited to build upon one another, not only will you have learned something important, interesting, and enduring about fungi during this brief time, you’ll be well prepared for the next topic presented the next time you open the book. Staying with the fungi volume, if you opened it no more often than once each working day while in line for your morning brew, and only read one section each time you opened it, in fourteen weeks you will have acquired a very strong general understanding of fungi, their morphology, diversity, reproduction, habitat, and conservation – all in the time that you might otherwise have piddled away on nothing you would likely remember at the end of the same time period.

And therein lies their particular value as an antidote to one of the great plagues of our modern age. In the same time that it takes to draw out a mobile phone, open a social media app, scroll for a few minutes, and perhaps leave a short comment or a couple of “likes,” someone carrying one of the Little Books of Nature can flip to where they left off and learn something important, interesting, and far more enduring than the latest meme or pseudo-scandal. Take for example the first chapter, “What is a fungus?” from the recently published The Little Book of Fungi by Britt. A. Bunyard. It is divided into six short sections, each two pages in length, each with lively, interesting, and helpful accompanying illustrations. Section titles include “How many fungi are there?,” “Primitive, but highly specialized,” and “Morphological classification.” At two pages in length, such topics are easy to read and begin to contemplate during the span of time it may take to await the making and delivery of your morning cappuccino or for the two people in front of you at the market to have their grocery items tallied, bagged, and purchased. And as the organization of the chapters and sections in each volume is carefully edited to build upon one another, not only will you have learned something important, interesting, and enduring about fungi during this brief time, you’ll be well prepared for the next topic presented the next time you open the book. Staying with the fungi volume, if you opened it no more often than once each working day while in line for your morning brew, and only read one section each time you opened it, in fourteen weeks you will have acquired a very strong general understanding of fungi, their morphology, diversity, reproduction, habitat, and conservation – all in the time that you might otherwise have piddled away on nothing you would likely remember at the end of the same time period.

So what subjects are thus far included in The Little Books of Nature? Presently numbering eight in total, the volumes are:

- The Little Book of Spiders by Simon Pollard

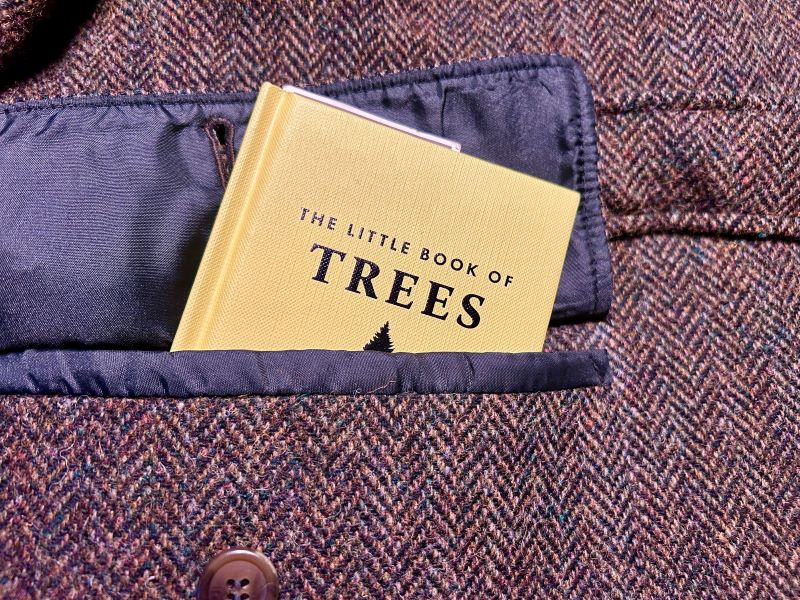

- The Little Book of Trees by Herman Shugart and Peter White

- The Little Book of Butterflies by Andrei Sourakov and Alexandra A. Sourakov

- The Little Book of Beetles by Arthur V. Evans

- The Little Book of Whales by Robert Young and Annalisa Berta

- The Little Book of Dinosaurs by Rhys Charles

- The Little Book of Weather by Adam Scaife

- The Little Book of Fungi by Britt A. Bunyard

Taken as a group, these eight volumes alone present any interested reader with a splendid general overview of some of the most dominant as well as charismatic and popular subjects in the study of natural history. Had the dinosaur volume existed when I was a wee lad, I would have read the covers off it, and committed every word and illustration to memory, irritatingly reciting its text or explaining its illustrations to anyone willing to indulge me long enough to listen. The volume on weather recently served me very nicely in opening my path toward a better understanding of that subject, and I’m presently toting the volume about trees about in my old tweed Norfolk’s right hip pocket (the left one contains my notebook and pencil – two other necessary EDCs, “every day carries,” for me).

When the Observer’s Book series was officially discontinued in 2003 following the publication of the The Observer’s Book of Wayside and Woodland, having had a long run beginning in 1937 with (what else) the The Observer’s Book of British Birds, one hundred volumes of it could be counted, including a ninety-ninth dedicated to the previous ninety-eight. As the Little Books of Nature have thus far seen eight volumes published, the question all but asks itself as to what future volumes may take as their respective subjects. While the nice people at Princeton University Press are keeping the kitty securely in the burlap regarding forthcoming volumes, my wish list is topped with volumes about fishes, rocks and minerals, ferns, wildflowers, mammals, and insects.

If we’re honest, we all have by now developed a psychological dependence on social media platforms that ranges from time-wasting to dangerously unhealthy in level of seriousness. And I fully acknowledge the unfortunate irony in that you likely found this essay as the result of seeing it posted to one or another of such online sites or the respective mobile apps. However if you did, please do the following: finish reading the article, close the app or social website, and go to your favourite bookseller (I recommend Cannon Beach Book Company if you don’t already have one of your own, and even if you do I still recommend them) and purchase one – or all – of these mind-feeding as well as mental health preserving little books and make a practice of carrying it with you throughout the day for reading for use during all those moments when you might otherwise have taken out your mobile phone to fill otherwise unoccupied time. It may be difficult to stick to the plan at first – bad habits are usually rather difficult to break – but relatively soon you’ll find yourself instinctively reaching for the book instead of your mobile. You may even find yourself looking for queues in which to stand or waiting rooms in which to… well, wait, just in order to have a few minutes of additional reading time for yourself.

Please visit the Princeton University Press website to learn more about all the books in The Little Books of Nature series, as well as their many other fine books.

As always, this review was produced without the use of AI tools in either the researching or the writing of it.

As always, this review was produced without the use of AI tools in either the researching or the writing of it.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.