There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

– Wm. Shakespeare, “Hamlet” (1.5.167-8), Hamlet to Horatio

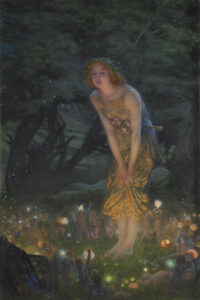

For as long as I have been interested in natural history, I have also been interested in folkore and mythology. And where once I was very rigid in the delineation of my studies between the two, as I have grown older, and especially as I have devoted a greater portion of my studies to the history of natural history, particularly the periods in history when the lines between what was and what was not, or what could not be, were not so starkly drawn as they are today, I have come to find the liminal spaces of nature to be of increasing interest. Perhaps that is natural as I am now closer to the liminal space of my own existence than I have ever been before and daily shall continue to be increasingly such until I one day enter into “what dreams may come.”

As such, I find myself increasingly contemplating how such things that have now largely disappeared from our disenchanted world were once very much a part of it. Let us not forget that Linnaeus himself included dragons, manticores, and sirens in the category Animalia Paradoxa in his Systema Naturae until the sixth edition of that book in 1748. And indeed, it hasn’t been so very long ago – and indeed in some portions of the world it still continues to be the case – that the existence of such creatures as faeries was commonly accepted. As recently as 1920, Arthur Conan Doyle himself, not only a man of letters but also, as a physician, a man of science, was very much convinced that they existed as a result of the photographs of what have become known as the Cottingly Faeries. We now know that the photographs were the result of the then relatively recently popularly expended technology of photography and how it could be used to depict staged scenes, but that does not diminish the fact that he truly found the pictures to be within the bounds of possibility.

When I began publishing The Well-read Naturalist in 2009, I did so because I wanted to bring attention to the many books I was regularly seeing in the area of natural history that I didn’t think were receiving the amount of attention they deserved. Since that time, I take great pleasure in knowing, from what I have been told, at least, that I have helped many people to find books that proved to them to be highly informative, very useful, or simply enjoyable. Through the years I have expanded the bailiwick of this publication to encompass not only books relevant to a modern day field naturalist, but to books about the history of natural history and the history of medicine. On occasion I also have include works of fiction that take one of these areas as a central theme. However I have been hesitant to include works, despite how interesting I may have found them to be, the inclusion of which I have feared might draw the ire of those who take great pride in being, shall we say, strictly scientific. Recent events in my life have since caused me to put aside such fears.

Therefore I am introducing a new section to The Well-read Naturalist with the title More Things in honor of the famous quote from Shakespeare’s Hamlet; a play and a sentiment both of which I very much admire. Here will be found works that seriously explore – and I can’t emphasize the word “seriously” sufficiently – subjects that can be described as being in the liminal spaces between the objective study of the natural world and those things that have long been reported to exist in it but for which we have no objective tools for proper enquiry, or histories of things that were once commonly accepted areas of study within natural philosophy that are either now all-but-entirely forgotten or so altered from what they then were as to make them effectively unrelated (astrology comes here to mind, as does lithotherapy).

Once again, I would like to make this perfectly clear – any books I include here are serious and rigorous explorations of their respective subjects. For example, I won’t be writing about How You Can Talk to Fairies, but I will be writing about Fairy Encounters in Medieval England; Landscape, Folklore and the Supernatural (if I can secure a copy of it, that is). I won’t be writing about How Crystals Can Help You Pick the Winning Lottery Numbers, but I could very well write about Speculum Lapidum; A Renaissance Treatise on the Healing Properties of Gemstones. I won’t be writing about Is Your Dog Psychic, but I likely will be writing about Black Dog Folklore; A Comprehensive Study of the Image of the Black Dog in Folklore. I won’t be writing about Harness Your Inner Dragon, but I will be writing about Introducing the Medieval Dragon (in fact, I already have).

I hope you find at least some of the books that shall be collected in this new section to be as interesting, as useful, and as enjoyable as you have perhaps found other books about which I have written in these electronic pages.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.