If human males and females spent a large part of each year living apart from one another (I don’t mean he spends hours in the den watching telly or out fishing with his friends, and she spends a similar amount of time with her book club or at the fitness center) but all of them wholly and truly separated for months at a time, how different would many of the most basic aspects of our society be? And perhaps more to the point, how would it affect us both individually and collectively? What would the negative effects be? Alternately, would there be positive effects, and if so what?

If human males and females spent a large part of each year living apart from one another (I don’t mean he spends hours in the den watching telly or out fishing with his friends, and she spends a similar amount of time with her book club or at the fitness center) but all of them wholly and truly separated for months at a time, how different would many of the most basic aspects of our society be? And perhaps more to the point, how would it affect us both individually and collectively? What would the negative effects be? Alternately, would there be positive effects, and if so what?

Of course, such a level of sexual segregation as this wouldn’t be conceivable outside of fiction when it comes to humans – we’re social creatures through and through stretching far in to the evolutionary past. However for some non-human animals, ungulates for example, the sexes living apart for substantial portions of each year is a normal course life. But this being the case, what does this tell researchers and wildlife managers about how to understand them and from that enact practices that best match how they live?

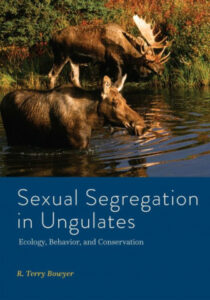

In his new book Sexual Segregation in Ungulates; Ecology, Behavior, and Conservation from Johns Hopkins University Press, Dr. R. Terry Bowyer explores why certain species of ungulates segregate, the effects this has on their social behavior, and how wildlife managers can apply the knowledge gained from investigating such questions to species and habitat management. And for those who may be interested in these same questions about animals other than ungulates, he occasionally expands his scope of consideration to include them (including humans) as well as plants.

Just as with all of the books in the Johns Hopkins University Press Wildlife Management and Conservation series, Sexual Segregation in Ungulates is written with an intended primary audience of those working in wildlife science and those studying to do so. However thanks to the didactic expertise and high quality of writing on the part of the author, and the keen work of the JHUP editors, this is a book that should also be of interest and value to a much wider group of readers, from both professional and amateur ecologists and naturalists to hunters and general wildlife enthusiasts.