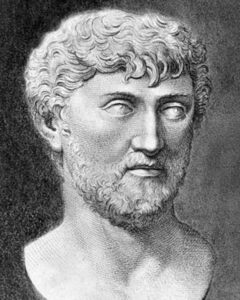

With such noteworthy books as Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson’s classic When Elephants Weep and more recently Peter Wohlleben’s The Inner Life of Animals that take the emotional lives of non-human animals as their subject having been published over the past few decades, bringing to a wide audience the idea that we are by no means alone in the psychological states we experience, I found this recently read passage in Lucretius’ first century B.C.E. poem’ On the Nature of Things worthy of note as further evidence that what we sometimes think of as a remarkably new discovery is actually very ancient indeed.

With such noteworthy books as Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson’s classic When Elephants Weep and more recently Peter Wohlleben’s The Inner Life of Animals that take the emotional lives of non-human animals as their subject having been published over the past few decades, bringing to a wide audience the idea that we are by no means alone in the psychological states we experience, I found this recently read passage in Lucretius’ first century B.C.E. poem’ On the Nature of Things worthy of note as further evidence that what we sometimes think of as a remarkably new discovery is actually very ancient indeed.

Nor in no other wise could offspring know

Mother, nor mother offspring- which we see

They yet can do, distinguished one from other,

No less than human beings, by clear signs.

Thus oft before fair temples of the gods,

Beside the incense-burning altars slain,

Drops down the yearling calf, from out its breast

Breathing warm streams of blood; the orphaned mother,

Ranging meanwhile green woodland pastures round,

Knows well the footprints, pressed by cloven hoofs,

With eyes regarding every spot about,

For sight somewhere of youngling gone from her;

And, stopping short, filleth the leafy lanes

With her complaints; and oft she seeks again

Within the stall, pierced by her yearning still.

Nor tender willows, nor dew-quickened grass,

Nor the loved streams that glide along low banks,

Can lure her mind and turn the sudden pain;

Nor other shapes of calves that graze thereby

Distract her mind or lighten pain the least-

So keen her search for something known and hers.

Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, from ch. 2, as translated by William Ellery Leonard