As many of you across the northern hemisphere who are afflicted with seasonal allergic rhinitis, much more commonly known as hay fever, have likely noticed by now, spring is here. For those in the Pacific Northwest, particularly anyone in or near the Willamette Valley – the self- (and accurately, I might add) proclaimed “grass seed capital of the world,” this is the time of year when those of us subject to hay fever experience violent and extended periods of sneezing interspersed with the overwhelming urge to claw our own eyeballs out of our respective heads as the pain of doing so would be less unpleasant than the perpetual itching experienced by allowing them to remain in place.

As many of you across the northern hemisphere who are afflicted with seasonal allergic rhinitis, much more commonly known as hay fever, have likely noticed by now, spring is here. For those in the Pacific Northwest, particularly anyone in or near the Willamette Valley – the self- (and accurately, I might add) proclaimed “grass seed capital of the world,” this is the time of year when those of us subject to hay fever experience violent and extended periods of sneezing interspersed with the overwhelming urge to claw our own eyeballs out of our respective heads as the pain of doing so would be less unpleasant than the perpetual itching experienced by allowing them to remain in place.

For those of who react allergically to grass, being able to identify one species from another is not only helpful, but in serious cases it can be potentially life saving as one thus knows when one is in the presence of a species that may cause a particularly severe respiratory reaction. The challenge is that the grasses are one of the trickiest of all the plant families to get sorted, and the sheer number of them here in Oregon and Washington – native and introduced – approaches four hundred when subspecies and varieties are included.

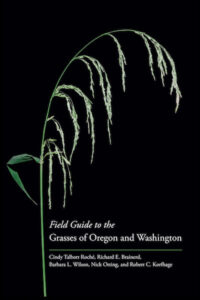

Thus, for all hay fever sufferers, as well as for those either professionally or recreationally curious to learn more about the numerous and challenging Family Poaceae as they exist in Oregon and Washington, it is indeed worth knowing that Oregon State University Press publishes a particularly helpful work on the subject: Field Guide to the Grasses of Oregon and Washington.

Created by the team of Robert C. Korfhage, Richard E. Brainerd, Nick Otting, Cindy Talbott Roché, and Barbara L. Wilson, this nearly 500 page tome includes identification keys, descriptions and photographic images of each species (both as they are seen in the field and under a microscope – including macroscopic images of important identifying features), habitat information, and range maps to all the three-hundred-seventy-six native as well as introduced species, subspecies, and varieties known to be found in the region.

As grass, as the introduction to this very useful book so clearly states, “is all around us,” its ubiquity leads to most people being “grass-blind,” Taking the time to learn how to distinguish even the most basic differentiating features of those species most often seen can open up a vast new field (sorry…) to all who are interested in plants, whether in order to find them or to simply know which ones to avoid. For those in the Pacific Northwest, this field guide is an essential resource in acquiring this knowledge.

Available from:

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.