I’ve been meaning to add a few new categories to The Well-read Naturalist catalog of subject areas for quite a while now. One, the history of medicine, you’ve already seen added with the recent feature review of Prof. Ben Mutschler’s Province of Affliction. The socond one is a bit more complicated – particularly as I’ve been uncertain what to call it.

I’ve been meaning to add a few new categories to The Well-read Naturalist catalog of subject areas for quite a while now. One, the history of medicine, you’ve already seen added with the recent feature review of Prof. Ben Mutschler’s Province of Affliction. The socond one is a bit more complicated – particularly as I’ve been uncertain what to call it.

As one who doesn’t see an interest in science and an interest in “things unseen” to be incompatible – so long as they are both understood for what they respectively are, I’ve long been interested in the intersection of the study and appreciation of the natural world with various practices of human spirituality. Indeed, human cultures – from their earliest known practices right up to our present day – are rich in spiritual practices that look not into the ether but directly at the physical world for their inspiration. From animism to Wicca, Shinto to modern Druidry, and even in some less widely known branches of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, nature and spiritual practice mixes freely.

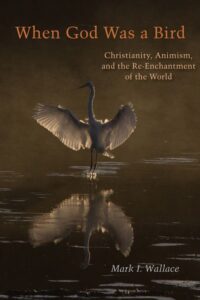

Thus, with this note reporting the recent discovery of Prof. Mark Wallace‘s When God Was a Bird; Christianity, Animism, and the Re-enchantment of the World, I would like to introduce another new subject category to The Well-read Naturalist dedicated to the idea so perfectly stated (in Act I, scene 5) by Hamlet to his friend Horatio upon the latter commenting that the appearance of the ghost was “wondrous strange:”

And therefore as a stranger give it welcome.

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

And in honor of which shall be cataloged as Heaven and Earth.

But back to Prof. Wallace’s book. Published in 2019 by Fordham University Press, this book caught my attention for it’s remarkably daring central proposition, that “[r]eligion in general, and Christianity in particular, appears to bear a disproportionate burden for creating humankind’s exploitative attitudes toward nature through unearthly theologies that divorce human beings and their spiritual yearnings from their natural origins. […] And yet, buried deep within the Christian tradition are startling portrayals of God as the beaked and feathered Holy Spirit – the ‘animal God,’ as it were, of historic Christian witness.”

Is it too much of a reach? Does it exceed his grasp? (Indeed, what’s a heaven for?) As a scholar specializing in the study of religion and ecology, Prof. Wallace seeks eminently positioned to take up such an inquiry. I’ll be very curious to learn what he has to present in support of his proposition.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.