Sir Winston Churchill once famously remarked “Dogs look up to you, cats look down on you. Give me a pig! He looks you in the eye and treats you as an equal.” At least so said Sir Anthony Montague Browne, Sir Winston’s private secretary. And for my part, I very much hope he did – not only is it a delightful line, it is at once both witty as well as containing a certain subtle truth.

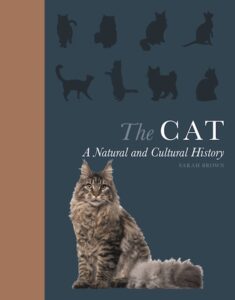

I bring this all up due to the recent arrival upon my desk of a new book from Princeton University Press: The Cat; A Natural and Cultural History by Sarah Brown. Published this past March, it joins the previously published, similarly formatted volumes The Dog; A Natural History by Ádám Miklósi from 2018 and Richard Lutwyche’s The Pig; A Natural History from 2019 to complete a Churchillian trio of books about some of our most familiar domesticated animals.

Professor Miklósi’s The Dog presents his readers with a examination of how a single species, Canis familiaris, has, since domestication, been selectively bred into more than three hundred recognizably distinct breeds, and how they function both physiologically as well as psychologically (with both other dogs as well as with humans). It is particularly in this last mentioned area – the psychological characteristics, and ability to bond with humans – where Prof. Miklósi’s writing particularly shines. As full professor and the head of the Ethology Department at the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary, and one of the three founders of the Family Dog Research Project, the “first research group to study the behavioral and cognitive aspects of the dog-human relationship,” he is one of the world’s foremost investigators into how dogs behave and think. As one who has had his heart wholly captured by a dog, this last aspect of the book is particularly poignant to me, as I’m confident it will be to all those who know and love dogs themselves.

Professor Miklósi’s The Dog presents his readers with a examination of how a single species, Canis familiaris, has, since domestication, been selectively bred into more than three hundred recognizably distinct breeds, and how they function both physiologically as well as psychologically (with both other dogs as well as with humans). It is particularly in this last mentioned area – the psychological characteristics, and ability to bond with humans – where Prof. Miklósi’s writing particularly shines. As full professor and the head of the Ethology Department at the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary, and one of the three founders of the Family Dog Research Project, the “first research group to study the behavioral and cognitive aspects of the dog-human relationship,” he is one of the world’s foremost investigators into how dogs behave and think. As one who has had his heart wholly captured by a dog, this last aspect of the book is particularly poignant to me, as I’m confident it will be to all those who know and love dogs themselves.

Co-author of The Behavior of The Domestic Cat – considered by many to be the definitive textbook on its subject – Dr. Sarah Brown takes up the examination of the natural and cultural history of her title subject in The Cat with Pseudaelurus, the ancient ancestor of the modern domestic cat that ranged through Europe, Asia, and North America during the Miocene. Developing the narrative from there, she brings the account into the modern period, presenting the anatomy, biology, and behavior of Felis catus in a manner that clearly explains so many of the remarkable attributes that make cats the beloved enigma they have become to so many of their human companions.

Co-author of The Behavior of The Domestic Cat – considered by many to be the definitive textbook on its subject – Dr. Sarah Brown takes up the examination of the natural and cultural history of her title subject in The Cat with Pseudaelurus, the ancient ancestor of the modern domestic cat that ranged through Europe, Asia, and North America during the Miocene. Developing the narrative from there, she brings the account into the modern period, presenting the anatomy, biology, and behavior of Felis catus in a manner that clearly explains so many of the remarkable attributes that make cats the beloved enigma they have become to so many of their human companions.

It is in this cat-human relationship that Dr. Brown focuses some of the most enlightening sections of her book. From the ancient Egyptians to modern-day “cat people” (a group to which I am allergically prevented from ever joining), these never-fully-domesticated creatures have long elicited fascination, affection, and curiosity, while to conservationists and some others they increasingly present challenges and in some cases threats to other species as a result of human-instigated overpopulation and subsequent neglect.

Turning from high-level academic research to the perspective of one who looks at his subject from a life-long-background of practical, on-the-ground animal husbandry, Richard Lutwyche’s The Pig takes up an in-depth look at the natural history of Sus scrofa, primarily Sus scrofa domestica – another animal that has been a part of mankind’s daily life since the Neolithic age when they began, essentially, to self-domesticate.

Turning from high-level academic research to the perspective of one who looks at his subject from a life-long-background of practical, on-the-ground animal husbandry, Richard Lutwyche’s The Pig takes up an in-depth look at the natural history of Sus scrofa, primarily Sus scrofa domestica – another animal that has been a part of mankind’s daily life since the Neolithic age when they began, essentially, to self-domesticate.

Mr. Lutwyche, raised around pigs since childhood and now held in highest regard as an authority on the subject of pigs by breeders around the world through his work with such organizations as the Gloucestershire Old Spots Pig Breeders’ Club, the British Saddlebacks Breeders’ Club, and the Rare Breeds Survival Trust, It is his work with this last organization that particularly caught my attention as I have long been interested in slowing the industrial-level agricultural homogenization of commercially farmed animals, the diversity of which has taken many centuries to develop.

In The Pig, Mr. Lutwyche examines his title subject’s existence “from the prehistoric ‘hell pig’ to today’s placid porker.” From their anatomy and biology, to their ecological and role in human societies, including their unique modern existence as companions to some while being food to others within the same society – a role, with admitted occasional exceptions (I’m told that one widely known primatologist keeps two cows as companion animals) and discounting the rapidly dwindling eating of dogs in small segments of some Asian cultures, that no other mammal presently holds.

Domestic animals are all too often neglected by those who study natural history, so it is with great pleasure that I see Princeton University Press bringing out such volumes as these that help to enlarge the understanding of them, their lives, the roles they play, and how the have come to be what they are today. For all who wish to continue their reading along these lines, Princeton also offers other similarly structured volumes, including The Bee, The Chicken, The Horse, and the announced forthcoming volume The Goat. I myself, since reading in Gary Bruce’s Through the Lion Gate A History of the Berlin Zoo about the attempted twentieth century “reverse breeding” and re-introduction of aurochs in central Europe, am hoping for a volume on The Cow.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.