Imagine that you’re a Seventeeth Century merchant of some means, and you’ve just acquired a new pet Nightingale. It’s a lovely bird with an exquisite song; doubtless soon to become an object of envy amongst your friends at your next dinner party. But as you sit admiring it, you are suddenly struck by a troubling thought: “What am I going to feed it; what do Nightingales even eat?”

Imagine that you’re a Seventeeth Century merchant of some means, and you’ve just acquired a new pet Nightingale. It’s a lovely bird with an exquisite song; doubtless soon to become an object of envy amongst your friends at your next dinner party. But as you sit admiring it, you are suddenly struck by a troubling thought: “What am I going to feed it; what do Nightingales even eat?”

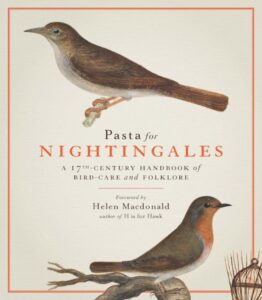

Should you be fortunate enough to have been in possession of a copy of Pietro Olina’s 1622 book Uccelliera, one of the first books written on what would eventually come to be called ornithology, you would find in its pages, amongst a remarkable collection of what was known at that time known about dozens of different bird species, a recipe for chickpea pasta that promised to solve your dilemma. And today, if you should be similarly fortunate to have the opportunity to read Pasta for Nightingales; A 17th-Century Handbook of Bird-Care and Folklore, you will discover in Kate Clayton’s English translation (the first ever made) of Olina’s book combined with the watercolor paintings from the Museo Cartaceo of Cassiano dal Pozzo that were the models of the engraved illustrations in the Uccelliera a fascinating insight into a time when works of natural history included at least as much folklore as empirical observation.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.