The feeling was really more of being struck the being stung. Standing on the hillside behind our Oregon home, I must have been 15 or 16 years old. I was performing some chore my father has set me to – clearing weeds most likely as I was using hoe when the incident occurred. I remember standing up from a stoop with the hoe in my left hand when suddenly something struck the back of my right with a perceived force that I swear knocked it backwards. My first thought was that I had been shot (we lived in the country) but looking down and seeing no blood, I was perplexed. It was only when the burning sensation and swelling began that it dawned on me that I had been stung.

Looking back, I think it must have been a yellow jacket. I likely drove the hoe blade too near a nest – or perhaps simply too near it as it hunted near the ground. I remember the burning lasting for quite some time – well over half and hour at least. Since that time, I’ve been stung by a variety of other insects, including an ant that fell down the back of my shirt in Panama and delivered an electric-shock-like jolt to my lower back sufficient to elicit from me a forcefully delivered, extremely blue expletive. While some stings were not nearly as bad as others, I wold not voluntarily wish to repeat any of them.

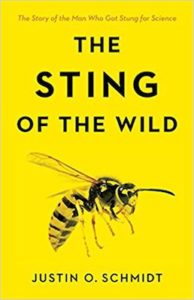

Justin O. Schmidt, on the other hand, has not only willingly allowed himself to be stung, he has made the effort to document, grade, and critique the various stings he has experienced and used them to construct the central theme of his book The Sting of the Wild; an act that positions him well past the qualifying line for the designation of “gonzo entomologist.”

Examining the central questions of how insects – specifically the members of the Hymenoptera (wasps, bees, ants, and sawflies) – evolved the ability to sting, why they do so, how stinging functions, and perhaps most interestingly, the concept and uses of pain itself, Schmidt guides his readers through a remarkable tour of things the vast majority of us would likely otherwise simply prefer to avoid, both intellectually as well as most particularly physically. Yet in Schmidt’s down-to-earth, friendly, and often self-depricatingly humorous prose, these often avoided – or simply unasked – questions become thought-provoking adventures into a remarkable and important aspect of insect life.

Why do the males of stinging species lack stingers yet still go through the motions of stinging? Does the physical size or longevity of lifespan of an insect have a relationship to the potency of that insect’s sting? What chemicals make up the venom used in stings, does it differ between species, and how does it function? And perhaps most intriguingly, why in some species is the act of stinging a suicidal one, resulting in their own self-evisceration? These and a host of other captivating questions make up the core of Schmidt’s first five chapters, which provide the basics of stings and stinging, and should be read both first and in the conventional sequence. However from there the structure of his book somewhat diverges from the norm.

Beginning with Chapter 6, “Sweat Bees and Fire Ants,” The Sting of the Wild becomes a collection of more-or-less independent accounts of particular Hymenopteran families, all of which may be read in any order the reader chooses. From yellow jackets and wasps, to bullet ants, to tarantula hawk wasps, Schmidt delves into the natural and life histories of, as well as his own experiences with, some of the, shall we say, most notorious stinging insects. (Of course, “notorious” is not appropriate to the previously mentioned sweat bees, nor is it to the topic of his final chapter on honey bees and humans.)

In closing, Schmidt presents his remarkable Pain Scale for Stinging Insects. Compiling the names, ranges, and descriptions of and pain level for eighty-three species of bees, ants, and wasps, this Scale is a fascinating insight into the astonishing variety of different stings. From the 0.5 pain level Club-horned Wasp (“Disappointing. A paperclip falls on your bare foot.”) To the 4.0 level Warrior Wasp (“Torture. You are chained in the flow of an active volcano. Why did I start this list?”), Schmidt’s documentation of the different stings he has experienced is as useful and thought-provoking as it is (the descriptions reading much like a wine list of pain) entertaining – although this last, to be sure, not so much so to Schmidt during the experiences themselves.

For all, professional and amateur alike, who are fascinated by insects, as well as those simply curious about one of the experiences with them that most of us will have at some point during our lives, The Sting of the Wild is an entertainingly written, highly informative book that is all-but-guaranteed to inspire questions in and pique the curiosity of even the most experienced of entomologists as well as the most casual of readers. Indeed, don’t be surprised after reading it if you find yourself not so much cursing as contemplating the feeling the next time you get stung.

Title: The Sting of the Wild

Title: The Sting of the Wild

Author: Justin O. Schmidt

Publisher: Johns Hopkins University Press

Format: Hardback

Pages: 280 pp., 13 color plates

ISBN: 9781421419282

Published: March 2016

In accordance with Federal Trade Commission 16 CFR Part 255, it is disclosed that the copy of the book read in order to produce this review was provided gratis to the reviewer by the publisher.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.