The scene: England in the middle ages. King Arthur and his faithful servant Patsy have just clip-clopped by two men standing by the road.

Large Man: Who’s that then?

Dead Collector: I dunno. Must be a king.

Large Man: Why?

Dead Collector: He hasn’t got shit all over him.

(Monty Python and the Holy Grail)

Once, not so very long ago, people all around the world lived with dung as a part of their daily lives. If they lived in the countryside, there was a dung pile somewhere nearby. If they lived in a city, the draft animals that provided the engines of transportation dropped it copiously in the streets. Then, of course, there was the little matter of all the human waste that needed to be managed in both these environments; and without central plumbing, that meant various “closets” and pots (often emptied directly into gutters, sometimes out of upper-story windows) in the city and simple latrines (at best) of varying forms in the country side.

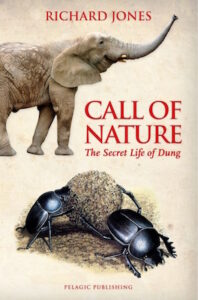

In a substantial portion of the world, such conditions have not changed significantly; however for those in the industrialized part of it, the separation from dung – our own as well as that of most other creatures – has greatly increased, to the point that many people now have become quite phobic about contact with it. And to be sure, as dung can act as a vector for a wide variety of unpleasant and even dangerous (to humans, at least) microbes, this estrangement from it has made the processes of how it is reabsorbed into the ecosystem largely a mystery even to many naturalists. Fortunately, Richard Jones is not in the least bit phobic nor estranged from dung. If he was, he couldn’t have written his fascinating and highly informative Call of Nature; The Secret Life of Dung.

For those who might not be familiar with Jones (which, given his prolific and engaging print and online publications as well as his regular BBC4 appearances, I wouldn’t expect to be a very large number of people by this time), he is an entomologist with an insatiable curiosity for just about any other area of natural history that catches his attention as well. With this, his most recently published book, it was dung – or more the point – the vast variety of creatures that live in, reproduce in, or are nourished by dung, as well as a larger circle of those that closely interact with such coprophilic species, that caught his attention.

Beginning with an overview of, if you will, the human social history of dung itself – a colorful and enlightening recounting to be sure – Jones moves swiftly on to the world within a dung pat. Spanning a range of investigations and “deep dives” into the excreta of elephants, to horses and cows, to dogs and even the odd human sample, readers are introduced to a parade of beetles, flies, moths and butterflies, and a few other special guests, all of which play a role in the breakdown and reclamation of dung into the environment, or at least derive some other benefit from it.

Admittedly, Call of Nature may at first seem to some like a collection of unusual, curious, and diner-party ruining trivia for naturalists. However as Jones progresses through the book, he methodically and subtly builds the tales of his explorations into an increasingly serious explanation of why dung is important to the ecosystem, and how our own activities in managing it are of far greater importance not only to us but to an astonishingly wide range of creatures as well. For just as the changes in how agricultural products were transported from farm to market (or processing facility) had the side effect of decreasing the available food for, and as a result the number of, House Sparrows, so the manner in which we manage dung is appearing to yield a change in the populations of species that for thousands upon thousands of years have played critical roles in the natural processing of it back into the ecosystem. Indeed, in pursuing his investigations into dung’s natural history, Jones does not confine himself to the present day but ventures back into the prehistoric past to assess what might have been the forms and biodegradation of dinosaur dung.

Like the very best of natural history books, Call of Nature, is an open invitation to the reader, as unlikely as such a thing could possibly be (and much to the utter horror of my at least up until now “naturalist curiosity tolerant” wife), from its author to get one’s hands dirty – with proper attention to washing up afterwards, of course. So much so that it may very well be the identifiable point of reintroduction to the English language of the word “dunging;” the intentional exploration of, and even search for, freshly deposited feces while afield. It is something Jones has described himself as having now done for years, and when young in he company of those who had been pursuing the activity for longer than he. And for those seeking to get started, following the text, an illustrated compendium of various leavings is included (the wombat dung by itself is worth the proverbial “price of admission”), followed by another section providing a similarly illustrated catalog of creatures to be discovered in or near dung samples.

Therefore, as will not surprise my regular readers and with potential domestic repercussions (see the aforementioned reference to my wife, above), I have already added a small trowel and rubber gloves to my standard field bag for when the opportunity presents itself for a bit of dunging. And even when I have not been possessed of sufficient time or inclination to get truly “stuck in” to a pile found during my ramblings, my reading of the copro-compendium appendix itself in Call of Nature has already proved quite valuable in the quick assessment of the calling cards for creatures possibly to have been found in the area.

Yet in all seriousness, as dung is and will always be, despite how ever-so-much we may try to pretend otherwise, a ubiquitous and important element of the life cycle of this planet, an understanding of it, of its creation, deposition, deconstruction, and re-assimilation back into the environment, is something we would all do well to cultivate. For truly, if we treat it, and all the creatures involved with its natural history, as merely expendable trash, attempting to manage it in a manner that is blind to the larger biological systems in which it plays important – sometimes critically important – roles, thereby permanently disrupting the cycles of its decomposition and reclamation, we could all quite literally one day find ourselves in deep shit.

Title: Call of Nature; The Secret Life of Dung

Title: Call of Nature; The Secret Life of Dung

Author: Richard Jones

Publisher: Pelagic Publishing

Format: hardcover

Pages: 303 pp., with 38 figures, 160 black & white illustrations

ISBN 9781784271053

Published: February 2017

In accordance with Federal Trade Commission 16 CFR Part 255, it is disclosed that the copy of the book read in order to produce this review was provided gratis to the reviewer by the publisher.