How do you begin to understand something you’ve never before seen – or perhaps even knew existed? Do you try to relate it to a thing about which you do know? Do you seek out the counsel of those you consider knowledgable, or those who have at least been identified to you as knowledgable? And what if this thing you are trying to fit into your understanding isn’t even something you’ve actually seen for yourself but only something that has been described to you; not in film or in photographs but only in words with perhaps a simple sketch as proof of its existence? How do you separate what might be factual from what could very well be fantasy?

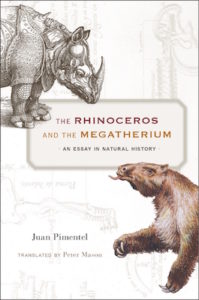

These are among the many questions Juan Pimentel poses in his book The Rhinoceros and the Megatherium; An Essay in Natural History. Taking as his subject the events surrounding two noteworthy specimens in the history of natural history – an Indian -or Greater One-horned – Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) carried alive by ship from India to Portugal in 1515, and the fossilized bones of a Giant Ground Sloth (Megatherium sp.) discovered and shortly thereafter shipped from Brazil to Spain in 1789 – as well as the creatures themselves, Professor Pimentel explores both the history and philosophy of natural history as it was in 1515, the ways in which it had developed by the end of the Nineteenth Century, and indeed, what it is today as a result.

Beginning with the rhinoceros, primarily identified in the book as Ganda, the personal name given to it that was derived from the common word used to identify it in multiple languages native to the creature’s original Indian habitat, Professor Pimentel approaches his narrative from not only the rhinoceros as third person object – as is commonly the perspective taken when discussing the subjects of natural history enquiries – but also from (imagined) first person perspective. Needless to note, this may throw up red flags for some readers (as it certainly did for this one); however these should not dissuade anyone from continuing on, for what the good professor is doing is part of the great classical tradition of essay writing. Recall that our English word “essay” comes from the Old French word essai, meaning “trial.” Professor Pimentel is, quite literally, trying upon the minds of his readers some of the ideas he has formed, as well as trying to find answers to additional questions yet remaining in his mind as the result of his studies.

To be sure, sometimes these trials send the narrative wandering seemingly far off the established path and deep into the proverbial weeds; however as all good naturalists well know, it is by venturing off into the weeds (the swamps, the caverns, etc.) that additional clues are found and discoveries made. Therefore when Professor Pimentel ventures into Sixteenth Century papal biographies, Portuguese colonialism, etymology, German art history, the early practice of taxidermy, or a myriad of other diverse topics, follow him closely with pencil and notebook in hand, for the discoveries he will make and share with you are numerous and should not be forgotten.

Of the many that were recorded in my own notebook are the shift in the very purpose of natural history itself (away from justifying the writings of the ancients to ascertaining facts based on observed evidence), the importance of Cuvier to the history of natural history, the significance of the scientific disputes between Jefferson and Buffon, and the story behind one of the most famous natural history illustrations ever committed to paper – Dürer’s now (and even then) oft-copied Rhinocerus. Indeed, prior to reading The Rhinoceros and the Megatherium, I had not thought of Dürer as a personage – let alone a key one – in the history of natural history illustration. That previous understanding has now most certainly been changed.

Then, of course, there is the matter of extinction, brought up in the consideration of the Megatherium. Let’s remember, the fossilized remains of this creature were discovered, assembled (incorrectly and in some respects almost comically), and studied in a world where the Judeo-Christian god had specifically created all that ever was, is, or would be; therefore what could be made of something once clearly a living being for which there was found to be evidence but that could no longer be found alive anywhere? Socially, the very idea of extinction, cautiously proposed by Buffon, had the power to shake the religious sensibilities of people in Eighteenth Century Europe in a manner every bit as thoroughly as Darwin’s ideas on evolution would when they eventually reached the pulpits of early Twentieth Century America. Enter Cuvier. (I will not venture further in this explanation but will leave the good professor to explain in his own words to those choosing to read the book for themselves.)

While it may initially strike some readers as perhaps a bit unusual in its rather holistic approach to its subject, The Rhinoceros and the Megatherium is a book much to be praised for the vast wealth of information its author brings to the narrative and for the astonishing number of questions it asks about topics spanning not only the history and philosophy of natural history itself, but of a host of others not normally brought into the study of these areas as well. In its pages, Professor Pimentel not only presents what is known about his subjects, but turns over the rocks under which additional possibilities might still be concealed and presents what he discovers there to his readers to essay in their own minds; a most worthy and time-honored method indeed.

Title: The Rhinoceros and the Megatherium; An Essay in Natural History

Title: The Rhinoceros and the Megatherium; An Essay in Natural History

Author: Juan Pimentel, translated from the original Spanish by Peter Mason

Publisher: Harvard University Press

Pages: 368 pp., 67 halftones

ISBN 9780674737129

Published: January 2017, originally published in 2010 as El Rinoceronte y el Megaterio; un esayo de morfologia historica by Abada Editores, S.L.

If you enjoyed reading this, please consider signing up for The Well-read Naturalist's newsletter. You'll receive a helpful list of recently published reviews, short essays, and notes about books in your e-mail inbox once each fortnight.