Strengthening the population of any bird species found to be declining in numbers is never a simple matter. Considerable research must always be done to answer a number of important questions – foremost among which being “What is causing the decline?” – if any plan implemented to reverse the trend is to have a chance of being successful. However what if the species in question has declined to such small numbers that it is no longer even found in the wild but only continues in captivity? The focus must then shift from strengthening populations to reintroducing them into their former range and habitat – and with this shift a host of additional questions come to the fore, particularly just what exactly the species’ former range and habitat was?

Such is the case with the California Condor. Once down to a population of just a handful of individual birds all living in captivity, thanks to a extensive program of protection and breeding, it has now risen to over two hundred birds living in the wild across southern California, Arizona, and Baja, Mexico. But was this the totality of their original range? It is this very question that Jesse D’Elia and Susan M. Haig address in their book California Condors in the Pacific Northwest.

From their examinations of the paleontologic record, the journals of early European American explorers to the region – such as Lewis and Clark, David Douglas, and John Kirk Townsend – and the legends and traditions of the area’s First Nations, D’Elia and Haig posit that these enormous birds once soared above the Columbia River and perhaps even as far north as British Columbia. However given the astonishing soaring range of a bird with a nearly three meter wingspan and the lack of substantial evidence of nesting in the region, the question of just what the condors might have been doing in the region must be addressed – something the authors do with superb scholarly care and judiciousness.

Of course, as there is considerable evidence of the condors once having been – regardless of reason – in the Pacific Northwest, and as they are most certainly are not now, the next question to be asked is why. To this inquiry D’Elia and Haig bring in a number of considerations, including the theory that the California Condor might simply be a relict (essentially, a left-over) species of the Pleistocene that was already declining in both range and numbers when humans first began to take notice of them. However as the known condor population appears to have declined in direct opposition to the increase of humans in their former range, the possible influences and secondary effects of this in-migration are considered at length.

Once all such questions have been considered and the evidence for their answers presented and thoroughly explained, the proverbial sixty-four-thousand dollar question in the minds of so many involved in California Condor conservation today is considered: should there be an effort to reintroduce a condor population in the Pacific Northwest? In their answer to this very important question the authors most brilliantly shine, for what they have to say to this is not only the culmination of all that they have presented in the book itself but is a superb example of the interweaving of objective scholarship and practical wisdom.

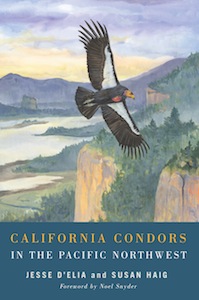

Title: California Condors in the Pacific Northwest

Title: California Condors in the Pacific Northwest

Authors: Jesse D’Elia and Susan M. Haig, foreword by Noel Snyder

Publisher: Oregon State University Press

Imprint: Oregon State University Press

Format: Paperback

ISBN: 9780870717000